by Nancy McCammon-Hansen

Tucked away in the southwest corner of Lindenwood Cemetery

is Jordan Crossing. Jordan Crossing is a section of the cemetery—Section 14-- set

aside for the graves of African-Americans who died in our city.

|

| Sign at Section 14 of Lindenwood Cemetery |

Among those interred there is Samuel Morris aka Prince

Kaboo.

“Sammy”, as he was called, was born a prince in 1873, the

son of a chief of the Kroo tribe in Liberia. Liberia at that time was in

conflict due to wars between rival tribes.

In a February 14, 1971 article in the “Journal Gazette”,

Sunday magazine editor Kenneth B. Keller wrote that “Kaboo was held in bondage

but his lot was better than other captives who were inducted into slavery.

Eventually he was redeemed by his father—for a price set by the rival chief.

But the resistance of Kaboo’s tribe was broken and its members were

increasingly imposed upon by belligerent neighbors. Tributes repeatedly were

exacted from the weakened people, the village subjected to lootings and growing

foodstuffs destroyed. At the age of 11 Kaboo was taken captive again and this

time he was used as a hostage to exact impossible demands from his people.

“Kaboo told of being threatened daily with thorny vines until he became too sick and exhausted to work. Then he was secured to stocks for the whippings and finally a grave was dug beside the whipping post as a warning of his fate.

“What he later described as a physical miracle enabled him

to steal away from his captors one night and slowly make his way to the coast.

Kaboo eagerly joined laborers on a coffee plantation near the capital city of

Monrovia. The work was hard but only a pleasure to what he had endured.”

|

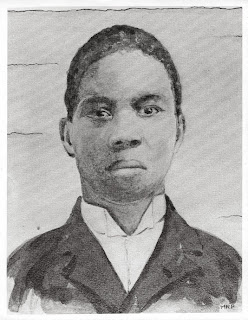

| Prince Kaboo...Samuel Morris |

It was there that he met a missionary named Miss Knolls who

had attended Fort Wayne Methodist College. Kaboo was her first convert to

Christianity and she renamed him “Samuel Morris” after the Fort Wayne banker

who had financed her education. Morris decided to become a missionary to his

people, likening his conversion to that of St. Paul. To gain the education he

would need to fulfill his goal, he sought passage to the United States and was

finally hired on as a crew member of a ship. It was a long voyage filled with

the captain’s wrath at his dark skinned “sailor” and sea sickness but

eventually Morris reached New York City and met Stephen Merritt, former secretary

to Methodist Episcopal Bishop William Taylor.

Morris had a profound effect on many that he met and is

credited with “no less than ten thousand conversions in the years of his

pastorate”. When he reached Fort Wayne, where the nearly bankrupt Taylor

University was located, he became a well-known speaker and helped to bring

badly needed monies to the school’s coffers. In addition to being a student and

preacher, he worked part-time to make enough money to bring Henry O’Neil, a

coffee plantation friend, to the United States.

In a History Center resource sheet written about Morris by Charles Sheets,

Morris is described as approaching his “education with the enthusiasm of his faith

because every effort was directed toward becoming a medical missionary to serve

the physical and spiritual needs of his people in Africa. The confines of the

Taylor campus at the west end of Wayne Street were never a limit to Sammy’s

activities. He spoke often at the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the

Berry Street Methodist Episcopal Church.”

Morris’ favorite Bible study was Chapter 14 of the Gospel of

St. John which reads in part:

“I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me. 7 If you really know me, you will know[b] my Father as well. From now on, you do know him and have seen him.” (NIV Translation)

“I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me. 7 If you really know me, you will know[b] my Father as well. From now on, you do know him and have seen him.” (NIV Translation)

But Morris’ time in Fort Wayne would be brief. He contracted

a cold in January, 1893, which turned into pneumonia and he died on May 12, age

20, at St. Joseph Hospital.

His death had an impact on Taylor that would not soon be

forgotten. Although his monetary worth at the time of his death was only $8,

and finances were still shaky at Taylor, faculty and students “found renewed

strength and zeal from the example of their late friend. Gifts of money came

from around the world from those who had been moved by the story of the African

youth in Fort Wayne,” according to Sheets. “…his life brought tens of thousands

of dollars to save a university which would go on to train hundreds of

missionaries to do the same work to which the humble African lad had

consecrated himself.”

|

| Marker provided by Taylor's Class of 1928 |

In 1908, Samuel Morris Hall was constructed on Taylor’s

Upland Campus. In 1928, his simple gravestone was replaced with a larger marker

by that year’s graduating class. And in October, 1965, Taylor University did a

public memorial service for “Sammy” Morris, led by Dr. John C. Wengatz, “a

veteran missionary who spent over 40 years in Africa, including 20 years in the

area where Morris was reared.” (Journal Gazette, Oct. 23, 1965)

|

| Jordan Crossing, All Saints Day 2013 |

No comments:

Post a Comment